In fewer than three weeks, on October 29, I’ll be releasing the following two titles:

- Time’s Up, Afton

- The Afton Morrison Series

In this post, I’ll be sharing a few details about each, as well as the complete (unabridged) afterword found at the end of Time’s Up, Afton.

Time’s Up, Afton

Afton contends with unwanted notoriety as she plots to kill vicious drug dealers and prepares for the last stand against her tormentor.

Time’s Up, Afton is the fourth and final book (part) in The Afton Morrison Series.

It will be available to purchase everywhere eBooks are sold (eBook only) for only $3.99.

As opposed to books one through three, each of which were novellas between 30,000 and 40,000 words, Time’s Up, Afton is a short, albeit full-length, novel at 51,000 words.

The Afton Morrison Series

Together for the first time, experience all four books in The Afton Morrison Series as one complete serial novel, including a bonus short story.

The Afton Morrison Series: Books 1 2 3 & 4, as the title suggests, is a complete collection (bundle) of the series, and it includes the bonus short story, A Book With No Pictures.

It will be available to purchase everywhere eBooks are sold for only $9.99.

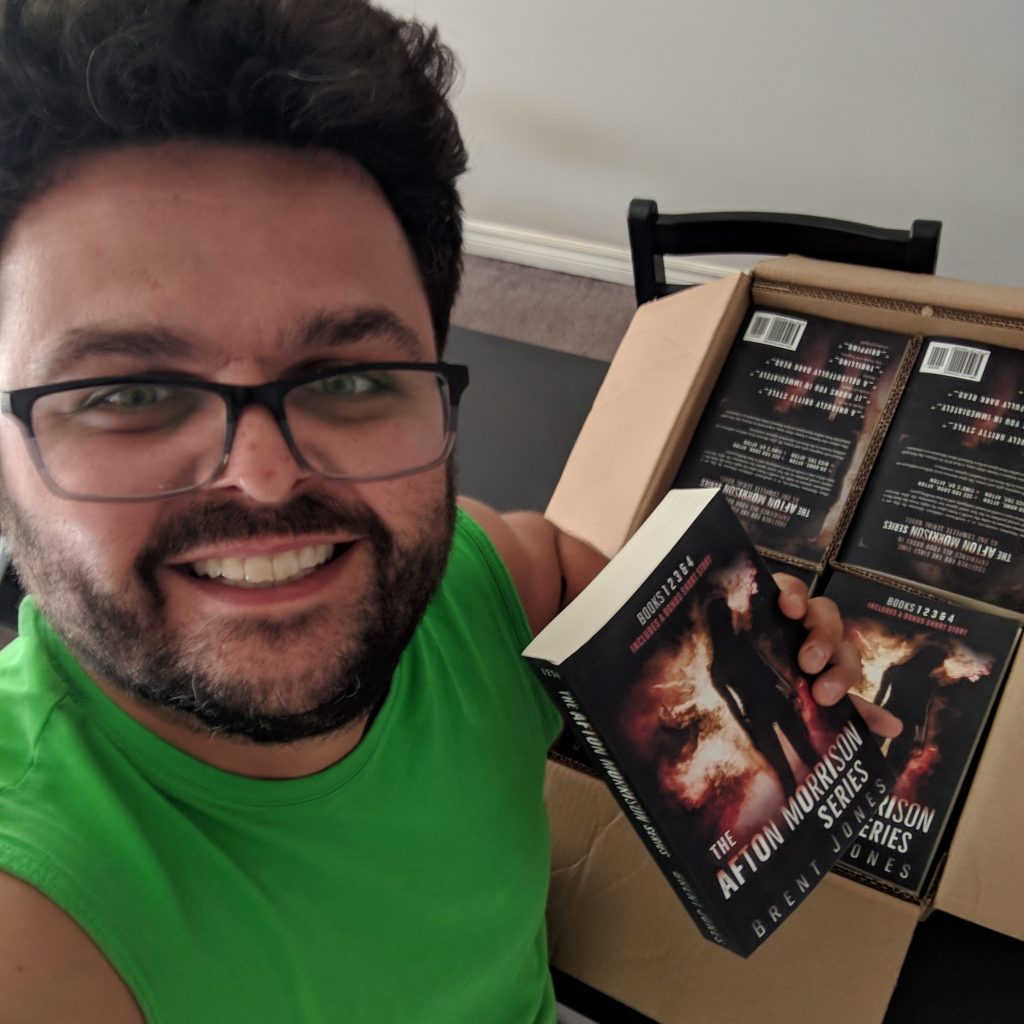

If not right on October 29, then shortly (a few days) thereafter, Books 1 2 3 & 4 will also be available in print (paperback) and audiobook formats.

For context, the audiobook will be in excess of twenty hours long, and the paperback version resembles a mid-size phone book.

Afterword by Brent Jones

Part of the fun of releasing this story as a serial thriller was watching readers consume one part at a time, make predictions, and draw their own conclusions.

While I don’t want to give away any of the surprises and twists to come in book four, I will say that a number of lingering questions readers have had will be explored and resolved.

For today, what I am sharing with you is the complete (unabridged) afterword, found at the end of Time’s Up, Afton.

While this won’t (conclusively) give away any major plot points or spoilers, it ought to answer a number of questions I’ve received from readers, as well as address some of the obvious references throughout the series to current political events and social trends.

My wife and I often watch reruns of Forensic Files before bed. It might sound morbid, but that show can put us to sleep in a matter of minutes. There’s comfort in routine, and Forensic Files is nothing if not formulaic and repetitive. If you’ve ever watched an episode, you know what I’m talking about. It begins with Peter Thomas setting the scene, describing how a body—most often a woman—was discovered decades ago in some shit town no one’s ever heard of. It’s right about then that Andréa and I will usually place our bets. “The husband did it.”

That’s because the husband always did it, or the live-in boyfriend, or the jealous ex-husband. There’s a certain pattern the show follows, one that seems to focus almost exclusively on crimes of passion and opportunity. And crimes of passion and opportunity, as Afton laments throughout the series, are predictable and boring. You can see it as each episode unfolds. Transparent motives, blatant lies, paper-thin alibis, and a trail of evidence that stretches on for a country mile. No, it wasn’t forensics that saved the day, even if the twenty-minute narrative would have us believe as much. It was the sheer stupidity of the halfwit assailant.

But it’s the predictable nature of each episode that offers cold comfort to viewers. A sense of security, even, having witnessed firsthand that law enforcement is all but infallible. In the end, the cops catch the bad guy, and we can all sleep safer at night. This pattern is so reassuring, so recognizable, that it can be found in other cable network shows with a focus on forensics and homicide investigations, such as Cold Case Files and The First 48.

I’m convinced that the reason these shows stick to cases with obvious motives is because cases without an obvious motive are near impossible to solve, even with the application of forensic sciences. It’s an opposing narrative that the viewing public might lose sleep over. Imagine if each episode of Forensic Files ended with some dazed local sheriff saying, “Damned if I know. We applied the latest in forensics, costing us years of manpower and millions of dollars, and we still couldn’t catch the bastard.”

I got to thinking one night, after watching Forensic Files, what would the perfect crime look like? If someone wanted to commit a murder—and I mean just for the sake of killing—how would he do it without getting caught?

The answer I came up with? Have no conceivable motive for doing the deed. Nothing to gain and no score to settle. The killer would need to choose his target at random, someone with whom he has no known ties or affiliations. And, if the killer has the presence of mind to do so, he ought to be meticulous afterward in his elimination of physical evidence. The murder weapon, for example, as well as his clothing, taking care not to leave behind strands of hair, footprints, tire tracks, clothing fibers, fingerprints, or bodily fluids. This second point pales in comparison to the first, however. Physical evidence isn’t much use if authorities are unsure whom to match it to.

Take, for instance, the case of Ted Bundy, who confessed to the murders of three dozen women over a span of four years. Was it that Bundy left behind no clues for police? No, of course not. His home and his car were teeming with it, yet he was able to carry on killing with impunity because no one had a reason to look into him. He had no obvious connection to his victims, and he had nothing to gain by their deaths. In the end, it was a minor traffic violation that brought him down. Crazy, right?

With that sentiment in mind, I wanted to write a story about someone cold enough—and just arrogant enough—to think he could pull off a string of perfect murders without ever getting caught. He’d be fascinated with true crime and convinced he could outsmart authorities. No, scratch that. Forget he and him. I wanted my cold-blooded murderer to be a murderess. Statistics suggest that male serial killers outnumber their female counterparts nine to one, and the killer I intended to create had to be someone nobody would ever suspect of murder. This led to the origins of Afton Morrison, a twenty-six-year-old children’s librarian in a small Midwestern town. A vegetarian with a pet goldfish who wears hipster glasses, ballet flats, and ankle-length skirts. An introvert with a working-class upbringing and a good education. A fan of romantic comedies, candlelit baths, long morning runs, and classical music. A productive member of society with no apparent reason to harbor violent tendencies.

Developing this character presented a couple of challenges, however. First, I’d been accused in the past of writing “weak” female characters, women that certainly wouldn’t pass the Bechdel test. And so, presenting a strong female lead—from a first-person perspective, no less—deserved some careful consideration. There are, after all, entire online forums dedicated to bashing male authors who attempt to write female characters, and perhaps rightfully so. I’ll never forget the moment that my editor shared with me the phrase, “She breasted boobily to the stairs, and titted downwards.” This, in her estimation, was an example of the type of thing I’d be best to avoid.

The second challenge on the horizon was the time frame in which I began writing Go Home, Afton. The first keystrokes occurred shortly before the Harvey Weinstein scandal made international headlines. Various hashtag-supported movements ensued, one of which I referenced in the title of book four. In the weeks that followed, countless women (and men) came forward to tell their stories. This gave me pause, as Go Home, Afton dealt with both perpetrators and survivors of sexual violence. Even though Go Home, Afton is fictitious, I wondered if audiences might think I was crafting this series to score political points. That I was attempting to capitalize on human misery, through virtue signaling, in order to sell more books and appear more relevant.

I was apprehensive, to say the least. So once I’d finished the first iteration of Go Home, Afton, I solicited feedback from a small group of female beta readers. I wanted to get their perspectives not only on the story, but on Afton as a character. Most of the feedback I received was constructive, allowing me, several months later, to craft a second, more powerful, version of Go Home, Afton. There was one beta reader, however, who almost (unintentionally) convinced me to not only scrap Go Home, Afton, but to give up on completing the series. The following is an excerpt from the notes she shared with me:

“I’m rather tired of the rape-as-a-plot-point trope that I’ve been seeing more and more recently. Women can be damaged in ways that don’t have to involve sex.”

This was an angle I hadn’t considered. The incident, as Afton refers to it, had occurred nine years before Go Home, Afton took place. The incident was part of Afton’s story, sure, in the sense that it informed her decision when choosing Kenneth Pritchard as a target. It made Afton more empathetic, too, when communicating with Tia Moore. It even served as a meaningful genesis for her alter ego, “Animus” Afton. But the incident was never meant to be a defining moment for her. Afton Morrison is who she is in spite of the incident, not because of it. I’d also never heard rape so casually conflated with sex, but that’s another discussion for another time.

Still, I had to wonder, was this beta reader on to something? Is “rape-as-a-plot-point” overused in fiction? Were there other readers out there who felt this way? Was this an example of lazy writing on my part? Had I reduced rape to nothing more than a simple literary device? If so, it confirmed my initial apprehensions, that I was writing a series that not only did a disservice to survivors of sexual violence, but to women everywhere.

Pairing her criticism with a nagging sense of self-doubt, I made a terrible mistake. Despite receiving mostly positive feedback from the rest of my beta readers, I became fixated on what this one person had told me. What followed was a period of grumbling and skulking around the house, mourning the untimely death of Afton Morrison. Gone too soon, before she ever had the chance to make her fictional debut. I wanted to write about her so badly that, in a manner of speaking, I did. Not as the unlikely protagonist of a serial thriller, but as a secondary character in a short piece I titled A Book With No Pictures, set the year before Go Home, Afton was supposed to have taken place.

A Book With No Pictures is a short, raunchy, comedic tale of dysfunction. Terrence, a middle-aged man, and someone whom Afton would, no doubt, describe as a degenerate nut sack, struggles to raise his gifted orphaned nephew in the fictitious small town of Wakefield. Looking back now, I realize that I wrote and subsequently published that short story almost entirely out of spite. It came through in the narrative, which I’d crafted to read as though Terrence was belaboring his misadventures to some random acquaintance at the bar. His speech patterns, tics, even his choice of curse words, sounded an awful lot like things Afton might say, even though his character was supposed to represent everything Afton hates about Wakefield. Terrence was written as the antithesis to Afton Morrison, right down to his poor personal hygiene, aversion to reading and physical fitness, distaste for nature, nutrition, and social issues, frequent substance abuse, disinterest in responsible parenting, and adorning sweatpants in public places.

A Book With No Pictures nonetheless became Afton’s first appearance in something I’d published. And in numerous instances, Afton’s exchanges with Terrence foreshadowed events in The Afton Morrison Series. For that reason, and that reason alone, when I publish the four books of The Afton Morrison Series as one complete collection this year, I’ll be including A Book With No Pictures following this Afterword.

Close to the end of last year, I was invited to be a guest at my wife’s monthly book club meeting. This group of women, with arguably more interest in wine than books, had just finished reading my second novel, Fender. Toward the end of the night, when there were only half a dozen women still present, I decided to bring up the premise of Go Home, Afton. Afton was still fresh on my mind, after all. I hoped to discover not only what they thought of the premise, but if they agreed that “rape-as-a-plot-point” had become a tired literary trope.

After a short exchange of ideas, one woman, who’d remained silent until that point, spoke up and told me, and I’m paraphrasing here, “There are five of us sitting in this room. Statistically speaking, one of us has been the victim of sexual abuse. If anything, I think there are too few stories that portray victims in positions of power. Sexual assault shouldn’t be discounted in anybody’s story, fictional or otherwise, just because some people are tired of hearing about it, or because it makes some people feel uncomfortable.” That was the exact shift in paradigm I needed to return to Go Home, Afton and complete the series.

It’s no coincidence that the main antagonist in this series is referred to as The Man in Shadows. Sure, it fits the imagery present throughout the narrative, as we see Afton float between two distinct worlds of her own, one light and one dark. But for most perpetrators of sexual assault, shadows are their most important allies. Their most notable strength (defense) isn’t spinning a good tale. It isn’t sheer physical prowess or rope or duct tape. It isn’t picking an isolated spot or planning some type of elaborate abduction. It isn’t their choice of date-rape drug or weaponry. It isn’t even intimidation after the fact. For most, it’s being able to hide in plain sight. It’s that too few survivors come forward, and too few survivors are taken at face value when they do.

I won’t pretend that The Afton Morrison Series was intended to be some complex allegory, because it most certainly wasn’t. I won’t pretend, either, not even for a minute, that I’m a strong enough author to craft something of such magnitude. This series was intended to be engaging and entertaining, and nothing more. But I will say, to any survivors of sexual violence reading this, please know that shadows can only exist in the absence of light. It is through the collective light of all survivors that predators are left with no place to hide. So, for the sake of making the world a better place, for the sake of doing good for others, please let your light shine bright. You’re not just another victim. You’re so much more than that. You’re a survivor, and you’re not alone.

Like what you read?

Feel free to share excerpts on Twitter:

...please know that shadows can only exist in the absence of light. It is through the collective light of all survivors that predators are left with no place to hide.Click To Tweet ...please let your light shine bright. You’re not just another victim. You’re so much more than that. You’re a survivor, and you’re not alone.Click To TweetYou can pre-order Time’s Up, Afton, book four in The Afton Morrison Series, here on Amazon for $3.99. As always, I recommend reading all four books in order. If you missed books one through three, you can get them here on Amazon for $3.99 each.

You can pre-order The Afton Morrison Series: Books 1 2 3 & 4 eBook bundle, including a bonus short story, here on Amazon for $9.99. The paperback and audiobook versions will follow on October 29, or shortly (a few days) thereafter.

Follow me on Twitter for updates, or subscribe to my email newsletter.

Thoughts?

Feel free to share them in the comments.